By the time I got to Mexico I had been dead for quite some time. It had taken me a while to piece it together, which was in itself how it had happened. I first knew that I had been dead when the ocean revived me the afternoon I arrived. Until then the grime of New York City, where I had been living, had been lodged in my pores. Where the hard, filthy pavements had sent shocks up my spine with each step I trod. It had been a long time since I swam in a warm sea. In Mexico, in the little surf town of Puerto Escondido in Oaxaca, the sky was expansive and bright and it reminded me of home and its unbounded spaces; it was a little like the coastal hippy enclave we traveled to on school holidays as teenagers, which itself was like a softening of the hard bodies and surfers of Bondi Beach where as a kid I used to take the 380 bus on weekends to and fro.

Mexico was home, but not home exactly. From soon after I landed in the very tiny airport I felt for the first time in the longest time like I didn’t want to be somewhere else.

Now, every day from my desk through the window I watch the parachutists fall back to Earth. Some of them float slowly, swooping, languidly paced, while others corkscrew straight down at terrific speed, passing by all the others. These last give me a kind of awful vicarious terror. Every day I hear their plane climbing to 13,000 feet, but I never see them actually jump out of it; they are too small and far away. I only see them once their multi-coloured chutes have bloomed and they are falling in a steady stream beyond the palm trees that line our street.

One afternoon with a visiting friend, we were watching the sunset on the beach when we looked up to see that they were going to land right on top of us; and they did, coming down and running along a strip of sand just beside us, whooping. One had misjudged the landing slightly and crashed down in the waves on the shore, emerging a moment later laughing, shaking the water from his hair, tangled in his lines.

Learning a foreign language you are often reminded of your new resemblance to a baby. This can be shockingly discombobulating from the lofty vantage of adulthood. You can neither comprehend, nor participate. All words to you are gibberish, a wall of indecipherable sound.

You are dependent on those few who understand your weird gestures and are able to kindly translate your needs. People will do things very slowly for you, many times, in the hope that you will comprehend. Over time you come to recognize sounds as attached to meanings, but mostly just are dumbstruck by how much a person knows without even thinking about it. Which is my left or right? Trouble in counting past 10. What is my name? What do I for a living? Lo siento, mi espanol es malo. How do I say, ‘yesterday’? Tomorrow, I am going to. Before, I used to be.

It dawns on you that in this language you might never tell a joke again and that your new personality is now one of almost constant, stony-faced concentration.

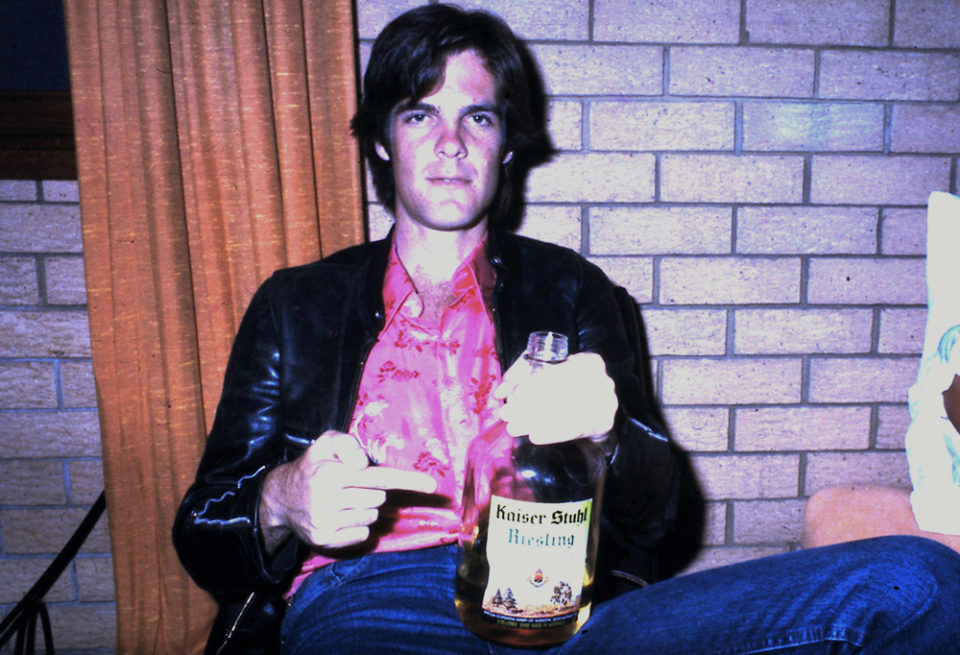

Photography by Elmo Keep

I asked a local friend to teach me something I needed to learn to say in Spanish.

Hey, come on! “Tienes que vivir tu viva.” You have to live your life.

Something else I’ve learned: roosters don’t crow only in the mornings; they do it at any time they feel like. In the afternoons their yodeling sounds deranged.

Coming home one early evening I saw a clutch of chickens scratching conspiratorially at the dirt in our street. One was running away from the others, very fast, peddling its little legs with its head down, like a missile. Once it was a safe distance away it stared back at the others with an unmistakable posture of contempt.

I will never know the precise sequence of events which preceded this incident.

Sometimes not being able to really speak is so nice. To only listen and not contribute is to realize that perhaps you’ve spent too much of the rest of your life talking.

In Oaxaca City I traveled with Ivano on a tour in the countryside that took us in total nine hours. This was a few days after I arrived in Mexico. We both rent studios in a house by the beach in Puerto Escondido, which is six hours away by bus through the winding roads that cross the mountains lush with vegetation and occasionally dotted with the brightly coloured adobe buildings of small communities.

Ivano is 65 and retired, from Southern Italy and having lived many years in Spain, his Spanish is perfect, though differs slightly from the dialects of Mexican espanol. He cannot speak a word of English, however, apart from a firm “No, no no,” (the universal) whenever I tried to pay for anything—I’m unsure if this is an Italian, Spanish or older retired gentleman custom, but arguing is ineffective. Between us we communicate with enthusiastic thumbs up, and a combination of the two pieces of Spanish that never fail to convey our feelings, “Perfecto” and “Cerveza” (beer, crucially the first word of Spanish I learned.)

Wherever we went people asked us, “Hija?” “No, no, mi amiga!” And I’d say, Si, mi amigo as we walked around the enormous girth of the world’s widest tree, its trunk 46 feet across, 2000 years old and found in Santa María del Tule.

We walked to the top of a petrified waterfall and stood gazing at the mountains in the distance. At the mescal distillery we got increasingly drunk on the samples we were continually given, especially a potent brew helpfully called “Fire” which was infused with chili and 50% proof. In old Aztec ruins we marveled at the completely straight lines of the perfectly laid geometric tiles found inside a tomb. We climbed back down the enormous stone steps and I wondered how they were ever moved from the quarry which was many miles away.

At these places I took a great number of photos of Ivano with his phone in which he struck an identical pose: hand on one hip, the other giving a thumbs up, smiling rosy-cheeked straight into the camera, his blues eyes crinkled into two half-crescents. Decades of laboring in factories have left his stocky arms and legs muscled like a much younger man’s, only a small pot belly (cervezas) concedes his real age. Every week he walks to the barber for the same neat, short haircut and trim to his moustache.

He looks at each photo and says, “Perfecto! Gracias,” and when we eventually get home in the evening will spend many hours sending them to his relatives on Facebook.

Puerto Markets. Photography by Elmo Keep

I had left New York the night before the 45

It took only the barest cheers from strangers lining the home stretch for them to be revived, the end within reach, and when the chants became cacophonous they beamed. We whistled and clapped and yelled “Great job!” as is the American custom and even at one point held out a cup of water, which was eagerly snatched away.

As the runners finished they were draped in a diaphanous poncho and soon steadily filled the park and the surrounding streets, a sea of blue shrouds.

As international sporting events go marathons are among the most globally diverse regarding entrants, who have often traveled from all over the world to run the city’s streets. We floated around, past the pond as the last of the fall leaves fell brilliantly coloured to the ground and I was filled with a terrible longing to not leave, even though I had been mostly miserable for almost every day I had lived there. I had made a quite large miscalculation as to the grit required to stick such a place out alone. Perhaps it was the ghost of someone I hadn’t shaken and all the past selves I’d left behind in Australia; possibly the city just wasn’t for me. Still it felt a triumphant moment to end on. The cresting tide of optimism was palpable.

I had been living in Oaxaca for less than 24 hours when the Electoral College, but not the popular vote, made Donald Trump President. He had campaigned on the promise to erect a wall between the United States and Mexico.

Photography by Elmo Keep

The house in Puerto is Gloria’s. Like Ivano she is also 65 and retired after a life spent as a civil litigator in Oaxaca City. She often sings to herself a song she wrote about the moon and the stars as she waters the garden and trims the many plants and flowers, her two dogs at her feet. She comes from an enormous family and there are often several of any number of relatives staying for a few days in the house, where they have come from Mexico City, or Oaxaca City or Monterey. When they are here, whenever they go out they ask me to come along. Sometimes on weeknights when going out to the salsa club Gloria will say, “Elmo! Come on!” When I decline because there will be work to do in the morning she admonishes me, laughing, “I think it is you who is the old woman.”

We cook meat from the market on the barbeque in the yard and Gloria’s aunts and cousins and sons and grandchildren pry from me my story and me theirs despite our (my) language barrier. Many nights spent late by the pool, and many cervezas later, with the very good tequila almost gone, we take turns playing each other our favourite music through the portable speaker. When they leave the house is quieter and we feel a small sadness for a day or so, but the house is never empty for long.

On a recent weekend, we were joined by a gaggle of only women relatives. There had been many particularly patient Spanish lessons for me as we gossiped about men. “My mother wants to tell you,” one of Gloria’s nieces, Estela said brightly, “That now you will always have family here in Mexico.”