We stand in a circle, palm to clammy palm, as the hum of the air conditioner gives voice to the space of the silence, bouncing off the whitewashed walls. I look around. All eyes, earnestly, remain closed. It is quite beautiful. I can feel their prayers on my skin. Worship has a friendly and optimistic flavour, it’s like the sunshine warming my back.

‘Can I pray for you?’ Dr. Wong inquires. I jolt a little, as her voice cuts through the stillness.

I guess? I hadn’t realised I needed praying for.

I am in Cambodia, in a mission house in the riverside town of Kampong Cham. I am uneasy. But, I’ll grant, I am happy. Years later, when my experience has dwindled to a mere anecdote, I amusingly exclaim that I accidentally joined a Christian mission. A charming gag.

But if I am being honest, my experience in Cambodia was meaningful and illuminating. I found myself stepping, fresh faced, into the world of evangelism, where, maybe because of the way I’d grown up, I felt misplaced. My family is Hindu, and by inference I am loosely, ‘culturally’ Hindu, the way many of us from the sub-continental diaspora are. And truthfully, I was skeptical of both the evangelical enterprise and religion’s place in today’s world.

I was studying in the library when I received the first phone call from Dr. Wong. I answered, hushed, aware of other students in the room. The international land-line buzzed in the background as Dr. Wong inquired with a sharp Malay inflection if I would accompany her on an upcoming pilgrimage. ‘Sure’ I whispered. ‘Okay’. Like falling off a log.

‘I actually do not feel comfortable with evangelism and preaching to other people’ I wrote in a later email to Dr. Wong. I had just read the mission itinerary, startled to see it heavily laden with preaching and prayer. ‘Not only am I not religious, but “preaching” is incongruent with my own personal philosophy’ I pressed.

Still, I wanted to participate. The trip was supposedly a medical mission and a great opportunity to learn about healthcare in Cambodia. So I sent off my email confirmation.

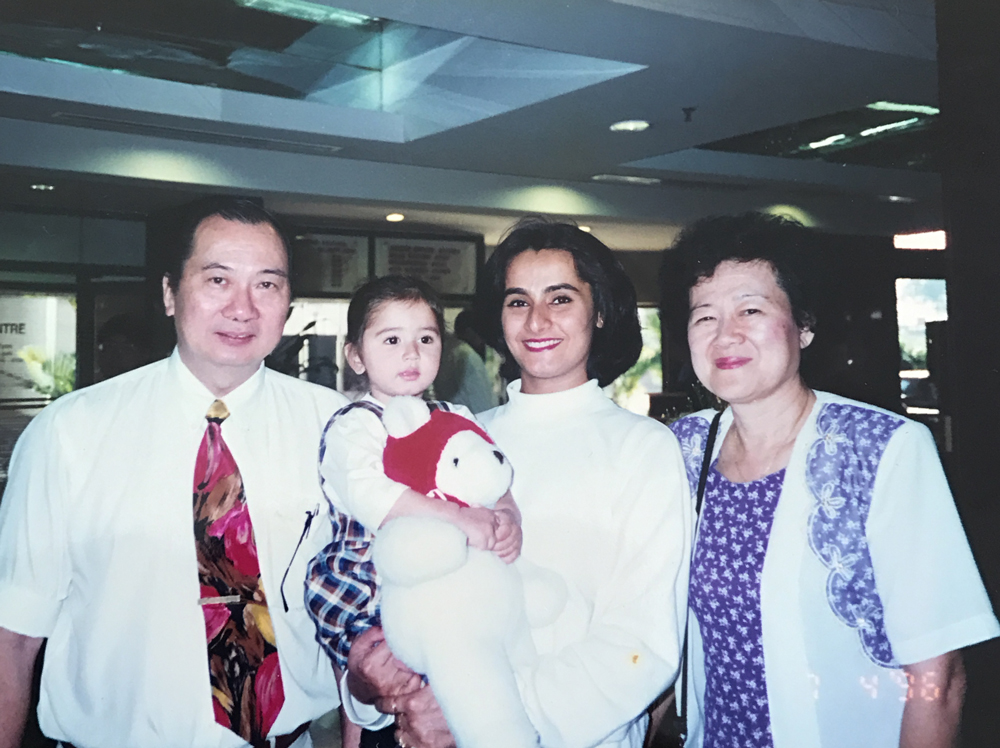

Dr Wong in her backyard.

I have known Dr. Wong for almost my entire life. I’ve seen scratchy film photographs of myself as a child, oversized heart sunglasses framing soft baby cheeks, grasping a giant stuffed bear in one arm as the other links around Dr. Wong’s shoulders. Snap. In the photo she grins broadly at the sleepy child perching restlessly on her hip.

Now, Dr. Wong and her husband have returned home to Malaysia. She fills her days tending to their beautiful, grand garden and watching midday Korean soaps with Maria the sweet Filipina maid. Occasionally, Dr. Wong sets off on a mission, pursuing her calling share the Gospel with the hapless herds who haven’t (yet) had the chance to welcome its verses. She didn’t mind my wariness, responding to my designedly firm email with a breezy ‘No problem! See you soon’.

So there I found myself, both bewildered and curious, standing in the living room of an air conditioned mission house in Kampong Cham. Being prayed for.

The primary objectives of this mission were to both set up a temporary first aid clinic to provide medical aid to Cambodians in rural areas, and to convert people to Christianity. Not in that order.

‘Well done team! We helped hundreds of people today.’ Reverend Malcolm trumpets. Standing in front of the congregation of volunteers, he leans forward excitedly. We are set up in the middle of a dirt road. There is red dust everywhere, it clings to the air. All backs are soaked in sweat.

‘But most importantly’ continues Malcom, ‘today we prevailed in our task to show 35 of these villagers the true light of the gospel, and they have turned to face the glory of Christ!’ The crowd erupts into cheers.

The spectacle in front of me is jarring. I had just seen a villager with a gangrenous foot be carted off to the local hospital. Surely no one believes it was more important to convert him than to provide him with medical aid. Right?

I suddenly become aware of my separateness from this congregation.

“You seem really tired” one of the volunteers asks gently when we’re slouching in the back of a van to return to town. She is a paramedic back in Australia. “Yeah, really tired” I retort.

But I am fuming. The sort of angry that sublimates into tears. I can’t seem to let go of a scene from the day, it loops persistently in my mind like a broken tape.

Dr. Wong is talking to an elderly villager. I look over from the pharmaceutical area of the clinic where I’ve been rostered. The villager is leathery and fragile, she speaks softly, under her breath. Dr. Wong asks her ‘Do you want to heal?’. The villager looks up ‘ចាស’ she sighs. ‘Yes’.

‘No’ Says Dr. Wong, suddenly impassioned. Raising her voice, she bellow’s ‘DO YOU WANT TO HEAL’? We all look over; the two women are fixated on one another. Eye to eye. After a pause the villager emphatically roars ‘YES’. Almost collapsing, she cries ‘ខ្ញុំចង់បាន JESUS’. ‘I want Jesus’. Her strained voice softens.

Back at the mission house that evening, each exhausted body slackens, still coated in a slick layer of sweat and dust. It’s been a long day. I excuse myself, I think I need a moment.

The thing is, I was an outsider as soon as I stepped off the plane. I was welcomed to behold the space belonging to the missionaries, but to view it from a distance. I was sanctioned to observe, without leaving pieces of myself behind. I wasn’t allowed to be angry. Or at least, I felt indebted, as though it was inappropriate for me to be angry. I was living, eating and working next to the beautiful beaming faces of my new Cambodian friends. How could I be anything but happy?

Feeling conflicted and dissonant, I found myself needing to understand the visceral reactions I was having to these experiences. I began to draw in the sketching journal I was travelling with, trying to find a shape and form for my feelings of discomfort. I drew myself underwater, dragging my feet through the sunken marshes in an old brass diving helmet. I drew that I was walking about with flames hugging my skin, not a figure around me even batting an eyelid.

I realised that I was doing that wonderfully conceited thing that humans invariably do. The thing that I always do. I was making it about me.

I was stuck feeling both ostracized for not having been ‘saved’ by Christianity myself, and feeling contempt for those who had been converted.

‘Of course you’re upset’, said my friend in an email. ‘Everything you’ve experienced in your life so far about being a brown person in a whitewashed world is resurfacing. You can relate to the locals because, even though for you, it wasn’t about religion, it was the same sentiment. Being told you are wrong.’

It is about that time in primary school when a girl mercilessly described my mum’s food as revolting. It is about me as a 10-year-old, haunted by the thought that the smell of curry was literally following me around, that my stink was the source of slander and gossip. It is about me feeling irregular and unlikely.

These feelings resurfaced when I put myself at the center of this experience. But when I took a step back, I saw something different. I saw joy and comfort. Community and belonging. I have vivid memories of ecstatic faces, warbling hymns at the top of their lungs in church. I saw more elation there than I have ever seen.

It may never be possible to completely cleave my own experience of the world from the lessons I grasp about living in it. I cannot not make it about myself. But sometimes there is a feeling you get in your gut. That this thing is a good thing.

‘Look at everything Jesus has done for me’, a sweet young girl from the mission house emphatically expresses. We are friends. ‘Do you love Jesus’ she asks me. I expect she already knows. I am a squatter in her community’s pious pastures. She looks at me expectantly, bright eyes unwavering.

‘Yes, I love Jesus’ I say.