Saving our knees, we stepped cautiously down the track through the casuarinas. The gradient was steepest here – sand and smooth rock covered in a slippery carpet of umber fir needles. The five children had already gone ahead, lithe and confident, racing each other to the bottom. We, the adults, were carrying the picnic food, towels, and swimmers.

On the last fifty metres of descent, where the sickle-shaped beach finally comes into view, our son Felix came running back up to us, breathless.

“There’s a big lizard down near the water, with a tin of cat food stuck on its head!”

We followed him, going left along the rocky shoreline of Broken Bay, to where four children stood around a large goanna, which was almost camouflaged on a flat slab of pocked grey sandstone. There was a yellow and black tin can sitting on its head – Black & Gold Seafood Platter Cat Food. The label was still bright, so it couldn’t have been in the sea for long.

Our muscly friend Geoffrey crept up quietly from behind and threw a big beach towel over the goanna’s body. Before it could shake itself free, he lay gently but firmly on top. From the other side, I took hold of the jerking head and held it still. Somehow the lizard remained calm; in the dark, being manhandled by unknowns.

Looking closely, I saw that the metal of the can had been cut with one of those claw-shaped openers, making a circle of jagged triangles. Someone on a cruiser or houseboat must have opened it for their waterborne cat and tossed it into the Hawkesbury. There were specks of blood next to each sharp point. My first tentative tug at the tin sent the lizard’s legs into a spasm and Geoffrey had to hang on like a rodeo rider. I tried again, gently, and after five anxious minutes, by pressing my fingers against the flesh near the sharp bits of tin, managed to prise the can free.

I jumped back, thinking that the goanna might snap at my hand, but it stood there motionless, blinking at the sunlit water. At last, it came to life and scrambled into the dry mulch under the casuarinas. I picked up the tin and put it in my bag.

Excited by this event, the children ran off down the beach to where low tide had revealed the crown of a rusted engine block, from a wrecked fishing boat. They spent an hour trying to dig it out, before they got hungry.

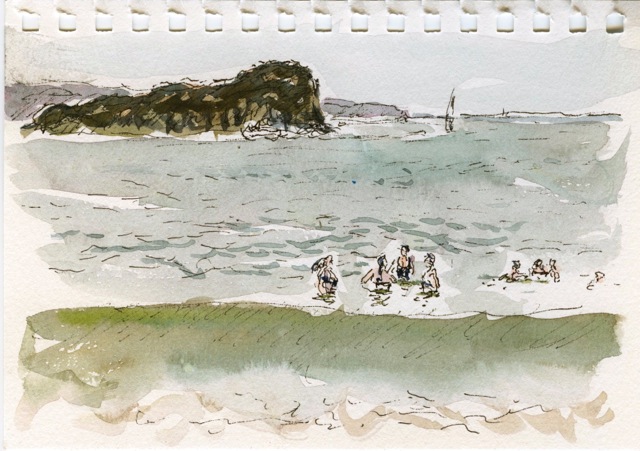

2013: Bathers, Flint and Steel, watercolour and pigment on paper. Artwork by Tom Carment.

There must be something about West Head that encourages such Sisyphus-like activity. In 1959 two park rangers heard someone digging, off the main road. It was Kevin Simmonds, the famous prison escapee, excavating a hole to secrete a stolen caravan. He tied the unsuspecting men to a tree, apologised, and stole their ute, continuing his flight from a force of armed pursuers. Simmonds was a handsome and charismatic young man who attracted a lot of public support as he evaded capture for nearly a month. He was caught in the bush near Kurri Kurri and, six years later, was found hanged in his cell at Goulburn Gaol.

The idea of burying a caravan in the bush of West Head to hide from pursuers captured my boyish imagination. I imagined it with a periscope. These days, knowing how hard and rocky that country is, the idea of digging a caravan-sized hole out there seems absurd.

Apart from a few settlements on its southeast shore, at Mackerel, Currawong and Coasters Retreat, accessible only by water, the West Head peninsula was saved from housing and development. It had strategic military importance – a big gun at its eastern end protected northern Sydney from naval attack.

There was once a single house with a tennis court at the western end of Flint and Steel, demolished in the late 1960s; and I met a woman on the track ten years ago who told me that as a child she’d lived in a cave halfway down, above the casuarinas, with her father. She showed it to me: a three-sided space, its dry sandy floor covered in lizard prints.

West Head was a place of great significance to the Guringai people, who created galleries of engravings on many of its smooth sandstone rock platforms – figures, shields, animals and fish. The making of these would have required incredible patience and labour – millions of small chips, rock on rock, an incremental linear progress, following a design best seen from three metres above the rock.

In my search for good painting spots I have several times stumbled across engravings of fish, small and large, and I have often found myself on the shoreline, sitting down beside shell middens.

I have wondered if the whole of Sydney was once equally covered in engravings and middens, and whether this peninsula is just a last untouched remnant of the whole.

Since 1975 I have walked all of the tracks on West Head but Flint and Steel remains my favourite. It starts from a grove of banksias near the eastern end of the West Head Road and winds down through one and a half kilometres of rocky bush to the water. There are angophoras near the top, and, at about halfway, a patch of palms in a small cleft of semi-tropical rainforest. All the way down you see jigsaw-shaped patches of water through the trees and beyond the rocks. I’ve seen this track burnt out by fires, damaged by storms, pink with wildflowers, and, more recently, invaded by tobacco weed.

On weekends when I’d ask our children, “Would you like to go for a bushwalk?” they’d always reply, in hopeful tones, “Flint and Steel, Dad?”

I guess it was a walk with a proper destination; a protected beach where you could swim, piles of driftwood to make shelters out of, creek water that snakes across the sand, perfect for earthworks and dams. There are circles of dried rock salt to sprinkle on your boiled eggs, and, when it rains, small caves in which to take shelter.

If my oldest son just wanted to lie in the shade of a banksia to read his fantasy novel for hours, no one would hassle him. Sunscreen and a swim were almost the only compulsory things. And the view out is wonderful – Lion Island, sitting in that large body of water, which moves from river to sea.

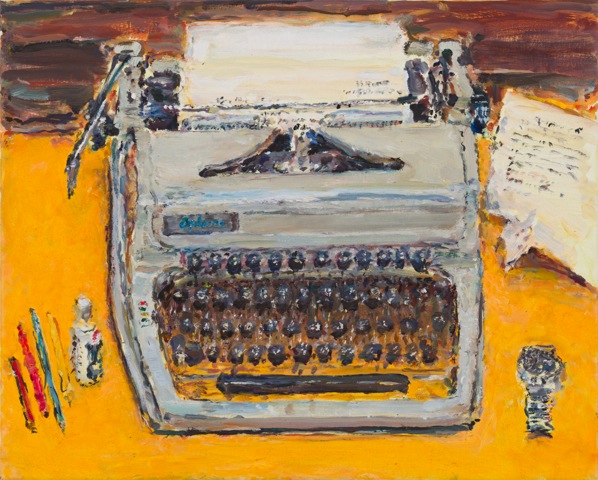

2017: Lion Island, gouache on paper. Artwork by Tom Carment.

Flint and Steel has a constant supply of fresh water too; a spring-fed creek, in a small cove three hundred metres along the rocks to the east. There’s a channel carved in the sandstone, long ago, by seafarers I assume, to ease the filling of barrels. These days, for fear of Giardia and other microbes, I zap the water I collect there with my battery-powered SteriPEN – easier than boiling it. No matter how dry the weather, there’s always fresh water trickling across that rock.

At breakfast one morning, my daughter Matilda, seven years old then, requested a day off school: “I want to go to Flint and Steel to paint with you.” It was nearly the end of the school year when they were mainly watching videos, so I said, “OK, sure.”

Two hours later we were sitting in the morning sun on the sloping rock above Broken Bay, side by side, painting pictures of Lion Island. After an hour or so we packed up our paper and paints, went for a swim and ate our salad packs and vegemite sandwiches under a banksia at the edge of the sand. On the drive home we bought a Christmas tree. Matilda said it was a perfect day.

In the casuarinas, on our way down to the water, an echidna had slowly crossed the track in front of us, like a good omen.

Tom’s favourite things for a bushwalk: Hat, Camelbak water bottles, woollen socks, SteriPEN, strips of old bicycle tube (for tying things on), contact cement (for when your boot sole peels off), a bag of pitted dates, Schmincke watercolours, small sheets of good watercolour paper, two sable brushes, a pigment ink pen, a small notebook and a pencil (for good ideas you get when walking).